This is not just *any* judgment: M&S in the High Court

I mean, it’s been hectic. Hasn’t it? These last few weeks. Are you keeping up? Are any of us. Turn your head for a moment, and you’ve missed everything from:

The Government-commissioned review into the London Plan which suggests a strong presumption in favour of granting planning permission for residential development on brownfield land (which the Mayor called a “stunt”); leading to

A consultation running until later this month on changing the NPPF (yes, again) so that, among other things, local planning authorities should give significant weight to the benefits of delivering as many homes as possible, especially where this involves previously developed land; to

Rolling local plan news - good (e.g. Greater Manchester), bad (e.g. Tandridge, Solihull, Spelthorne); to

Buckets of court judgments e.g. a failed 2nd challenge to the tunnel near Stonehenge, a succesful challenge to an Area Action Plan for a Garden Village in Oxfordshire, and a quashed consent for a solar farm in County Durham; to

New permitted development rights which, among other things, remove that pesky upper size limit for Class E to residential conversions.

But enough noise. For the moment, #planoraks, are you sitting comfortably? Feet up? Tea in hand? No particular place to go? Well then. Perhaps I can tell you a story:

In the late 1850s, a boy called Michael Marks was born in the town of Slonim - then part of the Russian Empire, now in Belarus, at the confluence of the Shchara and Isa rivers. In the early 1880s, just like around 150,000 other Eastern European Jews of his time (including, as it happens, my great-grandparents), Michael left home, bound for the hope-filled shores of Victorian England. To the mighty city of Leeds, no less. To work alongside other Jewish immigrants at a clothes manufacturer called Barran.

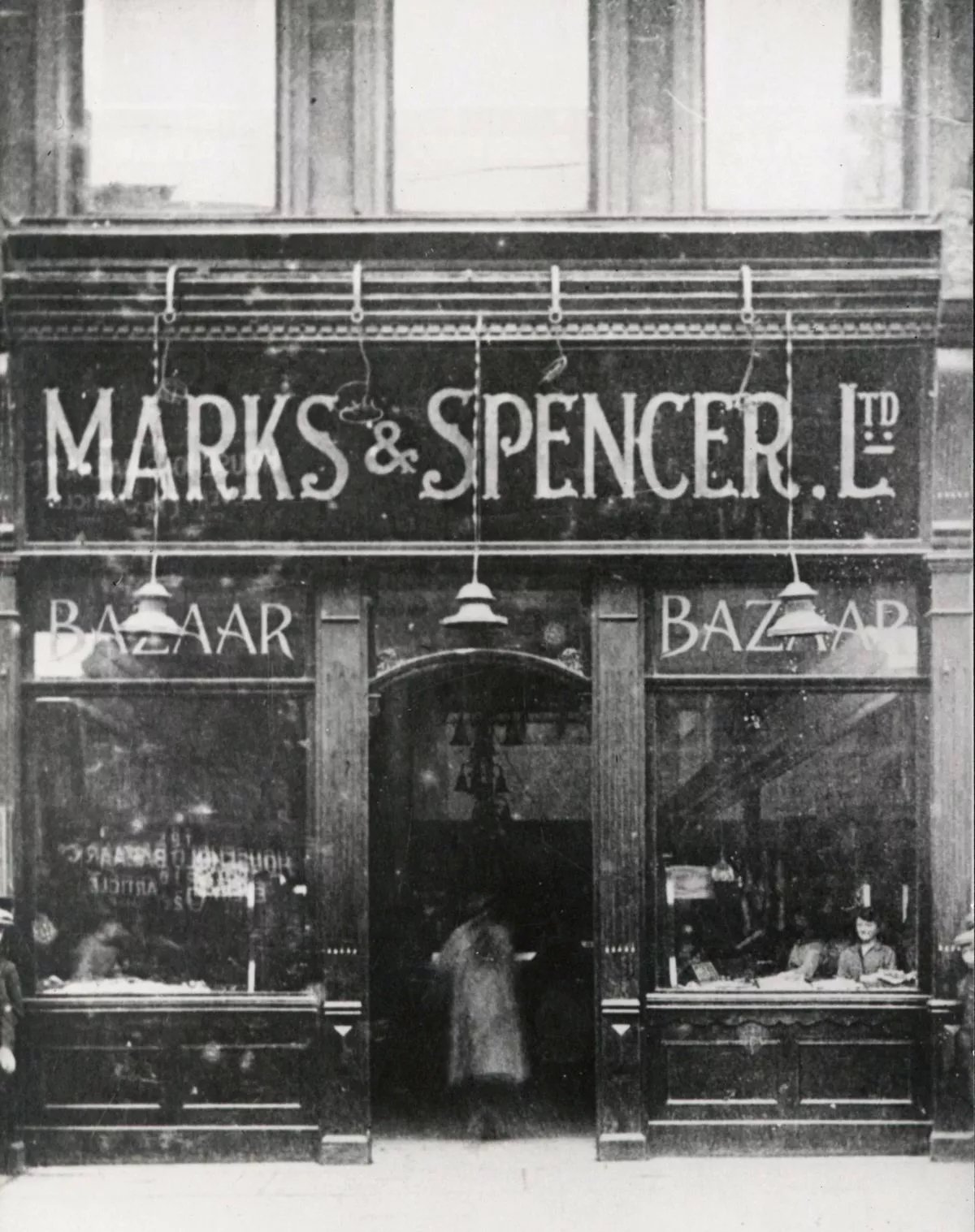

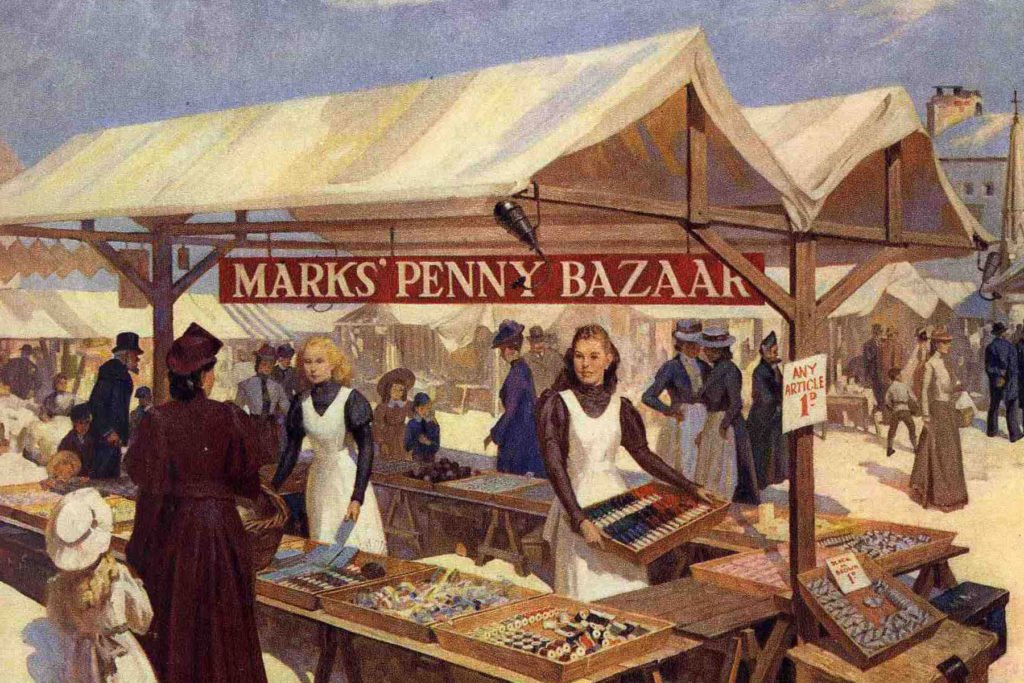

But Michael had something just a little magical - ambition, vision, and a keen eye for a deal. He started buying and selling clothes. Which went well enough to allow him to open a market stall in Leeds in 1884 - using the admittedly catchy slogan: “Don't Ask the Price – it's a Penny”:

Things kept growing - to market stalls all over Yorkshire, and then Lancashire. It got so big that in 1894 Michael decided he needed a partner. But who? In the end, he took an investment of £300 for half his business from a local cashier called Thomas Spencer. And, well… you know the rest. As Alexander Hamilton once rapped: “immigrants: we get the job done.”

M&S has, obviously, been part of our national furniture for well over a century. It’s still one of our most important retailers. They have also for the last 20 years done a consistently good and indeed award-winning “New York Deli” pastrami sandwich on rye (which some of us die-hards wrote in - actually wrote in - to vote to make permanent after a glorious 2006 stint as “sandwich of the month”). And, I mean: Percy Pig. Colin the Caterpillar. Yum yums. These are national institutions.

Anyway. Michael and Thomas moved their fledgling business into London at the turn of the 20th century, and their biggest store is now near Marble Arch on Oxford Street in the City of Westminster, in London’s swinging West End. Next to Selfridges. One of the highest profile, most accessible locations in the country - in the heart of London’s Central Activities Zone, and a designated International Centre. M&S have been on this site since the first half of the 20th century. The principal building fronting Oxford Street is called Orchard House which came along around 1930 as a speculative office building, which was only later converted into Percy Pig’s national HQ:

Today, the M&S Marble Arch store covers a higgeldy-piggeldy arrangement of 3 buildings - Orchard House, Neale House and extensions at 23 Orchard Street:

None of those buildings are listed (an attempt to get Orchard House listed was rejected by Historic England). None are in a conservation area. Albeit, of course, we have some lovely listed buildings nearby, including Selfridges - that glamorous Grade II* Beaux-Arts style homage to the stylings of late-19th and early-20th century Chicago department stores, commissioned by Gordon Selfridge himself. Here both stores are together - a view lots of you will recognise:

Anyway. The M&S buildings weren’t built for retail. Over half a century later, they’re long in the tooth. They’re inefficient, not structurally fit for purpose, expensive to run and no longer up to fulfilling their role as M&S’s flagship. So. In 2021, M&S applied to to demolish them, and to upgrade to something bigger and better.

What did they have in mind? A state-of-the-art building designed by a team led by Fred Pilbrow (who has designed, among other marvels, the Heron Tower and the Crick Institute at St Pancras) that looks like this:

Sadiq Khan’s Greater London Authority liked the scheme. Historic England did not object. Westminster officers supported it. And Westminster’s members went for it too - they resolved to grant planning permission in November 2021, in part to give Oxford Street a much-needed post-pandemic boost in the face of all those depressing, back-to-back American Candy stores.

Buuuuuut… not so fast. In June 2022, in the face of objections from - in particular - Save Britain’s Heritage, Michael Gove called the application in. Which led to an inquiry in October-November 2022, and a Secretary of State decision in July 2023 here. A very experienced Planning Inspector called David Nicholson - an architect by trade, and he of the Tulip decision fame - had liked the design, thought the heritage impacts were outweighed by the scheme’s powerful public benefits, found that there was no viable alternative to demolishing the buildings, and recommended that planning permission be granted. But in the end, Michael Gove disagreed with all of ‘em - Westminster’s officers, its members, the GLA, the Inspector - and refused permission.

And since then… well, things haven’t been going so well:

The M&S boss called the decision “nonsensical” and “utterly pathetic” and off they went to challenge the decision in the High Court. Where - to cut a long story short - after a February 2024 hearing, Mrs Justice Lieven produced a judgment yesterday: here. Mr Gove’s refusal = quashed. On no fewer than 5 grounds. 😬. The Government’s position was described by the Court variously as “nonsensical” and “astonishing”. Sounds like that M&S boss may’ve been right. 😬.

The decision will now need re-taking - whether by this Secretary of State or (gulp) his successor. And, in consequence, planning once again finds itself splashed all over the national news.

So what have we learned? From all this drama. Have we learned anything?

Well, for one thing, this is yet another example (here’s looking at you, Cranbrook) where a Michael Gove decision to overturn the will of the local planning authority and the recommendation of his inspector after a long inquiry has been quashed in the courts. Turns out if you’re going to go out on a limb and disagree with everyone, you’d better have verrrry clear and robust reasons for your decision.

Still, the headline-grabbing point is about carbon. And what national policy says or doesn’t say about it. So here’s a ready reckoner:

Do it up, or knock it down?

We are - you may’ve noticed - in the throes of a global climate emergency. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and carbon in particular, has become a huge issue for the planning system.

London has been blazing that trail. The London Plan has a policy which requires major development to be “net zero-carbon”, and is supported by London Plan Guidance, Whole Life-Cycle Carbon Assessments and on the circular economy. The first principle in that guidance is that “retaining existing built structures for reuse and retrofit, in part or as a whole, should be prioritised before considering substantial demolition, as this is typically the lowest-carbon option.”

NB retention is typically the lowest-carbon option. Not always.

Does national policy prioritise reuse and retrofit in the same way? Not quite. What is now §157 of the NPPF is drafted at a higher level:

Now, M&S was a case where all the parties - including the objectors, SAVE - agreed that something had to be done for M&S to continue on Oxford Street. Everyone agreed that the existing buildings were inefficient, and the new building would be highly sustainable in operational carbon terms. Still, SAVE’s big point was that M&S had failed to justify a rebuild over a retrofit (see e.g. here). M&S said that they’d considered all the alternatives, and there was no viable or deliverable refurbishment option. The buildings, so M&S said, had to go (and, indeed, they had a permitted development right to knock them down in any event).

That was agreed with by the GLA, who said that:

“GLA officers accept that the retrofit and reuse of buildings can play an important role in meeting national and London Plan carbon reduction targets; however, neither Policy S12 nor Policy SI7 of the London Plan prohibits demolition, with the WLC Assessments LPG and Circular Economy LPG requiring priority consideration to be given to the retrofitting of buildings. GLA officers are satisfied that the applicant has given sufficient consideration to the retrofit and refit of the existing buildings and in this instance on balance the buildings can be demolished.”

The Inspector found there to be “harm through substantial quantities of embodied energy in the demolition of three sound structures and the construction of a new, larger building” but ended up deciding that “there is no viable and deliverable alternative and that refusing the application would probably lead to the closure of the store, the loss of M&S from the Marble Arch end of Oxford Street and substantial harm to the vitality and viability of the area” and that “the difficulties of the three connected buildings render the viability and deliverability of any refurbishment in such doubt that redevelopment is the only realistic option to a vacant and/or underused site”.

But what did the Secretary of State find? He said that:

“there should generally be a strong presumption in favour of repurposing and reusing buildings, as reflected in paragraph [157] of the Framework.”

And then ended up disagreeing with everyone - Westminster, the GLA and the Inspector - to find that:

“the evidence before him is not sufficient to allow a conclusion as to whether there is or is not a viable and deliverable alternative, as there is not sufficient evidence to judge which is more likely. The Secretary of State also does not consider that there has been an appropriately thorough exploration of alternatives to demolition. He does not consider that the applicant has demonstrated that refurbishment would not be deliverable or viable and nor has the applicant satisfied the Secretary of State that options for retaining the buildings have been fully explored, or that there is compelling justification for demolition and rebuilding.”

Permission refused.

So what did Mrs Justice Lieven make of all of this? We can be honest, can’t we. Between friends? Well, alright then: she wasn’t very impressed with Mr Gove’s decision. She really wasn’t. She decided that:

The NPPF has no “strong presumption in favour of repurposing buildings”. So the Secretary of State got that wrong. Big time. And, you know… not to say “I told you so”, but I do seem to remember saying something about this last year. The Judge said that:

“The SoS has not applied the policy, he has rewritten it. This then leads to him applying a test, or policy hurdle, through the rest of the DL which is based on his misinterpretation of the policy.”

😬.

So. Get the message? When the NPPF wants to create a presumption about something, it has to tell us so. Like it does elsewhere.

Mr Gove didn’t give good enough reasons for disagreeing with the Inspector on (a) whether there were viable and deliverable alternatives to the scheme, or (b) why harm flowing from the loss of investment if permission was refused, and the loss of a strong retail attraction at the western end of Oxford Street, beyond Selfridges, would only attract “limited” weight. The Court recalled what had been said in other cases, e.g.:

“Where the Secretary of State disagrees with an inspector, as he did in this case, it will of course be necessary for him to explain why he disagrees, and to do so in sufficiently clear terms. He must explain why he rejects the inspector's view. He must do so fully, and clearly.”

Unfortunately, in this case… not so much.

The offsetting requirements in the London Plan relate to operational carbon, and not embodied carbon. What’s all this about? The Judge explained:

“In policy terms, carbon consequences are divided into those emanating from the construction phase, and those from the operation of the development. Embodied carbon is generally referred to as that from the construction phase, including demolition. These analyses are necessarily complex and can go into ever greater levels of detail, but in broad terms construction impacts can go back to the construction of the materials, the transportation emissions, and the construction of the building itself. Operational impacts cover matters such as the heating and cooling of the building.”

In the decision, Mr Gove became, the Judge said, “thoroughly confused” and assumed - wrongly - that the requirement for carbon offsetting applied to embodied carbon and not just operational carbon. The Judge described this approach as “transparently wrong”, “nonsensical” and “astonishing”. 😬.

What does it tell us? That retrofitting is an important and positive focus. But not in every case. And not at any cost. And if the Secretary of State wants to presume strongly in favour of something, he’s actually going to need a policy which says that. Meanwhile, London’s local authorities are beating him to it. The City of London’s latest draft plan describes itself as “retrofit first”, and Westminster is about to consult on following suit.

Boy oh boy. So many years, millions of pounds, a planning application, an inquiry, and a high court hearing later, M&S have lots of national headlines, but still no planning permission for their new building. What a wonderful system we have, eh. What, you wonder, would Michael Marks make of it all.

I hope you’re staying well, #planoraks. Enjoy your Percy Pigs, remember to do what Mrs Justice Lieven says, and always to keep your reasoning “full” and “clear”, and most of all… whatever else you do, try your level best to #keeponplanning.