🏆 The #Planoraks 2024 - the new NPPF 🏆

It’s beginning to look a lot like plan-mas. You’ve all heard the buzz. Whispers in the corridors. Christmas lights twinkling, and speculation in the air. Who’s up, who’s down? What’s in, what’s out? The great and the good being quizzed on the Sunday shows. Inane, deliberately misleading newspaper columns. Heck… apparently, they’re even letting planning lawyers on the Today programme. Yes. It can only be [drumroll purrrlease…]

The 5th annual #Planorak awards.

[Pause for applause]. Thank you. Thank you so much.

Oh yes… plus the new NPPF’s out. Don’t forget that. Sure, it’s no #Planorak awards. But still, right? We should cover it I think. Cover it we shall.

So, to business, friends. Look sharp - it’s awards season. Polish up your shoes. Straighten those bow-ties. Don your poshest of posh awards-night clobber, arrange the taxis, let’s meet for pre-drinks, and then join me on the red carpet for the most lavish, no-holds-barred, entirely-made-up awards event in the UK planning law blog-o-sphere firmament.

And what a year it’s been! The judges were festooned with top-drawer nominations in 2024. A bumper crop. Non-stop hits. And to cap it all, this last week, the frantic excitement of a rush of last-minute entrants - a national scheme of delegation, a key Court of Appeal case on section 73 consents, a series of massive Secretary of State approvals on high-profile sites like the M&S on Oxford street (links here), the PM going to Pinewood studios describing the planning system as “a blockage in our economy that is so big… it obscures an entire future… […] A chokehold on the growth our country needs… Suffocating the aspirations of working families”. 😬. Add to all of that… Simon Jenkins. The man himself. One of our most illustrious previous winners. At pains to concede, after having claimed (falsely) that local people will no longer have any control over where they live, that “of course, the state must have some care for the housing of its citizens”. Aw. So generous of Simon - a citizen lucky enough to have been housed not once but twice. “Some care”. Who could ask for more?

Well, we could. #Planoraks could. And more we have received. Because, like a bolt from the blue, it’s arrived. Weeks like this are what this blog was made for. Here we have it, folks: a brand-spanking-new NPPF.

Let us start, as always, with (a) a deep breath, and (b) some hyperlinks:

The new NPPF itself: here.

The obligatory tracked changes version: here.

New “local housing need” numbers for each authority: here. Plus a verrrrrrry helpful table here (h/t Paul Smith for this one) showing how the numbers have changed in each LPA since consultation.

The Government’s response to the 11,000 consultation responses, which helps explain why we’re getting all of this: here.

The long-awaited new housing delivery test scores: here.

Updated PPG on lots of things including plan-making, viability, housing supply, housing and economic needs. Watch this space for more PPG to come on lots of important topics, including the green belt reviews and the grey belt all coming in January 2025. More of which below.

£15 million authorities who want to do green belt reviews: here. P.s. - as we’ll come to - lots of authorities are going to need to do green belt reviews whether they want to or not!

To get caught up on the background and what was consulted on and why, have a look here, here and here.

So. Before we start doling out the gongs, how about a run-down of what we have? A whistle-stop tour. There’s way more than can comfortably be squeezed into a single blog post. So you’ll have to let me be a bit selective. OK? Are you sitting comfortably? Here we go:

New housing numbers

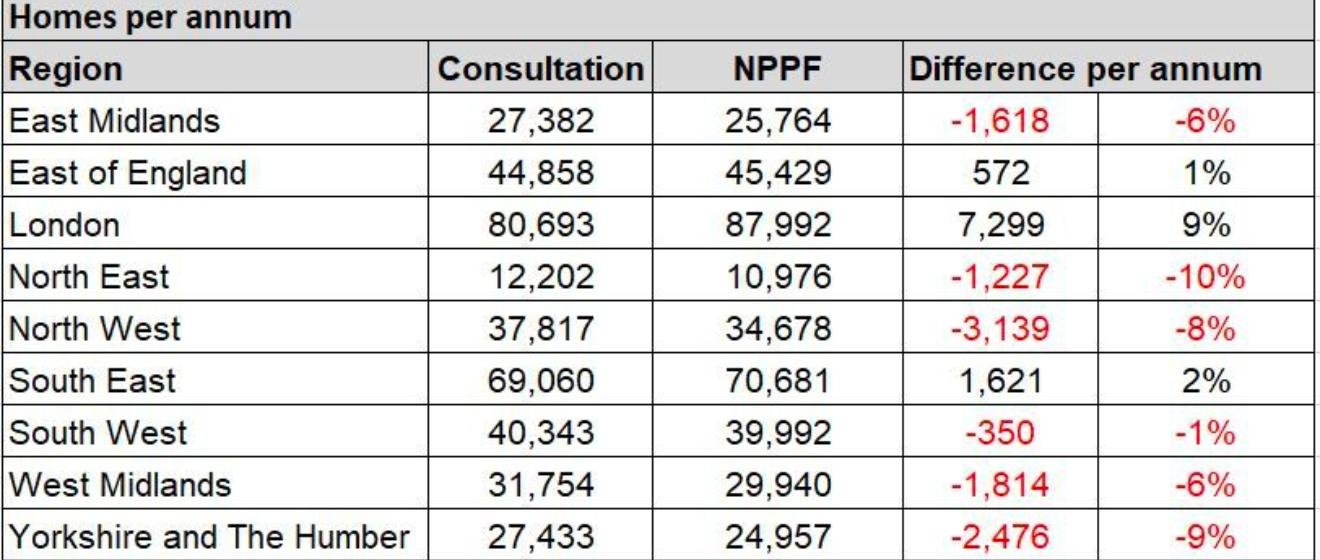

As discussed, the new formula notionally gets us to permission for 370k new homes nationally a year. Which is what we need (at least) to come close to 300k actual completions. There’s been a technical tweak to affordability in the approach that was consulted on - explained here. So the numbers are all slightly different. The broad thrust is the same. Numbers go up overall (and sometimes quite a bit) in every region in the UK, bar London (albeit they’re up in London from the 80,000 consulted on to almost 88,000 now). Still - as I explained here - the London numbers are still very considerably above (i) what’s in the London Plan (and what housing land supply will continue to be judged against until at least March 2026), and (ii) what London is actually delivering. Regionally - the situation looks like this:

Transitional provisions:

The new NPPF, and these bolstered numbers, have no application to emerging local plans which:

Are submitted for examination on or before 12th March 2025. If these plans have a housing target of less than 80% of the standard local housing need number, Councils will be “expected to begin work on a new plan” under the new system as soon as the relevant provisions of LURA come into force “in order to address the shortfall in housing need”. If those plans end up failing at examination, well… they then have to face the full rigours of these housing numbers. And even if that pass examination and end up being adopted, they may be facing what is, in effect, a 6 year housing land supply requirement before too long. We’ll come back to that.

Reach Regulation 19 consultation on or before 12th March 2025 when their housing requirement is at least 80% of the standard local housing need number.

For decision-making, the NPPF kicks in immediately.

There’s lots of other transitional provisions which lay the groundwork for strategic plans of the future, but… we’ll come back to them when there we actually have more strategic plans to talk about…

The presumption

A “presumption in favour of sustainable development” that is structured in broadly the same way it now, albeit, as part of the so-called “tilted balance” at §11(d)(ii) (on which, see here) we now have to have particular regard to a range of things including locational sustainability, design, making effective use of land and affordable housing when that balance is being struck. All of which are, let’s be honest, important things we’d need to be thinking about anyhow.

Plus, under §11(d)(i), footnote 7 policies now need to provide a “strong” rather than a “clear” reason to refuse. The change in wording is, so the Government say, about “strengthening” the presumption’s wording. Which may, we’ll see, provide a bit of flex around things like e.g. flood risk sequential testing - to which we’ll return.

Housing land supply

4 year supply is gone [in a savage blow to planning bloggers everywhere - what a waste]. Immunity against 5 year supply challenges for recently adopted plans - also gone.

Buffers to be applied to housing requirements are back - 5%, or 20% when there has been significant under-delivery (i.e. a sub-85% score on the housing delivery test).

Plus - a fascinating new policy which might help balance some of the ills caused by the transitional provisions above: from 1st July 2026, a 20% buffer is added for authorities which have a requirement adopted in the last 5 years against an older version of the NPPF at a level 80% or less than local housing need. The effect of this is to make it harder - much harder - for plans in authority areas that squeaked by under the current rules to maintain an adequate housing land supply. In effect, they’d need to demonstrate a 6 year housing land supply from 2026 to stay afloat. And, in consequence, it becomes more likely that some of these freshly adopted plans that squeak in under the transitional provisions are deemed out of date by §11(d) and footnote 8 of the NPPF before the ink on them is even dry.

Another tweak - buried into the transitional provisions at §232, when authorities do have a 5 year housing land supply and are passing the housing delivery test, then:

“policies should not be regarded as out-of-date on the basis that the most up to date local housing need figure calculated using the standard method set out in national planning guidance is greater than the housing requirement set out in adopted strategic policies, for a period of five years from the date of the plan’s adoption.”

What’s interesting about this is the last clause. You get 5 years. After that, there’s a strong implication that policies should be deemed “out of date” - so activating the “presumption” policy at §11(d) - after 5 years post-adoption even when there’s no obvious housing shortfall simply on the basis that the plan requirement is lower than the standard method.

Brownfield / previously developed land

At §125(c), an important and very helpful shove in the direction of approving brownfield schemes within settlements to meet needs through a new presumption policy:

“Planning policies and decisions should […] give substantial weight to the value of using suitable brownfield land within settlements for homes and other identified needs, proposals for which should be approved unless substantial harm would be caused”

This takes a different - and better, I think - conceptual approach to consultation, which said that this kind of development would be acceptable “in principle”.

Plus, the definition of previously developed / brownfield land expands to include “large areas of fixed surface infrastructure such as large areas of hardstanding which have been lawfully developed”. But it’s a no to including “glasshouses”.

Green Belt

What hasn’t changed? Lots, e.g. the fundamental purpose of the green belt, and the 5 green belt purposes live to fight another day. Green belt boundaries should be reviewed through local plans in exceptional circumstances, same as now. The test for granting permission for inapprioraite development in the green belt at §153 NPPF (aka “very special circumstances). Same old.

What has changed? Also lots:

A big ticket item (I’ll come back to it below) - §146 says that exceptional circumstances include cases where:

“an authority cannot meet its identified need for homes, commercial or other development through other means. If that is the case, authorities should review Green Belt boundaries in accordance with the policies in this Framework and propose alterations to meet these needs in full, unless the review provides clear evidence that doing so would fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt, when considered across either the area of the plan or the wider Green Belt as a whole.”

When reviewing those boundaries, authorities should turn first to previously developed / brownfield land, then to so-called “grey belt” (more of which in a sec), and only after that to non-brown non-grey green belt. So long as those areas are locationally sustainable.

We have a broader carve-out for previously developed sites in the Green Belt than we did before - as per the consultation, if your scheme “does not cause substantial harm to the openness of the Green Belt” - which Inspectors have already held is a high bar indeed to cross - then you’re no longer “inappropriate development” in the green belt.

Grey Belt

OK. Let’s walk this through:

First, what does it mean:

Under the new NPPF definition, it means:

“land in the Green Belt comprising Previously Developed Land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143. ‘Grey belt’ excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.”

Big changes from the consultation draft? Well, there’s been a lifting of the bar. We’re no longer after land which makes a “limited” contribution to green belt purposes. Instead, we’re after land that doesn’t make a “strong” contribution (as per the wording in the consultation document that accompanied the draft NPPF). So - land which makes e.g. a moderate contribution…. maybe even a significant contribution?…. that land is capable of meeting the test.

Plus, of course, it’s no longer all 5 of the purposes we’re interested in. For “grey belt”, it’s only purposes (a), (b) and (d). The big point, then, is that contribution to purpose (c) is excluded from the definition of “grey belt”, i.e. the purpose of "assisting in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment”. Why this change? Because, in a nutshell, it would risk whipping the rug out from under “grey belt'“s feet as an effective policy mechanism. Almost all green belt is at least deemed countryside (i.e. outside settlements). Any buildings would encroach into that countryside. So almost all green belt is fulfilling that purpose, almost by definition. If that purpose become a bar to “grey belt”, you’d barely have any “grey belt”.

Second, once we know what it means, what’s the point of having it?

For plan-making, as above, the point about “grey belt” is that you turn to releasing it first before non-brown non-grey green belt.

For decision-taking, things get interesting:

If your site is “grey belt” plus a few other things - to which we’ll come - then your scheme is no longer “inappropriate development” in the green belt. So what? Come on. You know the so what. So (a) you don’t require justification with reference to very special circumstances under §153, (b) there’s no clear reason for refusal under green belt policy under §11(d)(i) and footnote 7, and so (c) assuming no other slip ups, you pass onto the tilted balance in your favour at §11(d)(ii) NPPF. It’s a seismic reversal of the policy test that applies to hundreds and hundreds of sites all over the country.

So… that’s the prize. How do you get there? In addition to being grey belt…

Your development can’t “fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt, either across the area of the plan or the wider Green Belt as a whole” - a bar that most individual development schemes are not going to meet.

You need to be in a sustainable location.

There has to be a need for your scheme (e.g. in a housing case, a failure of the HDT sub-75% or a sub-5 year housing land supply).

And, for housing schemes, you need to pass the golden rules……..

“Golden rules”

When do these so-called “golden rules” kick in? Any time you’re proposing “major development involving the provision of housing” in the green belt - either through allocation or planning application.

So - to be clear - these aren’t relevant for non-housing development. But they are relevant even for previously developed sites in the green belt when you’re promoting housing.

What do they include - the more straightforward ones involve securing any necessary infrastructure improvements (e.g. through a planning obligation), and providing publicly accessible green spaces which “contribute positively to the landscape setting of the development, support nature recovery and meet local standards for green space provision”. Then we come to… affordable housing….

Affordable housing: the blanket 50% prescription from the consultation is gone. In its place is a more sophisticated mechanism:

New local plans are expected to set affordable housing targets for green belt allocations above non-green belt sites, and at a minimum of 50% unless viability testing shows it would make development unviable.

However, unless and until that happens… so in the meantime where there’s a plan target in place, you add 15% above that target, capped at 50%. Where there’s no plan target in place, you default to 50%. And note, from the new viability PPG - no viability assessment for now for green belt sites to knock this down:

Where development takes place on land situated in, or released from, the Green Belt and is subject to the ‘Golden Rules’ set out in paragraph 156 of the National Planning Policy Framework, site specific viability assessment should not be undertaken or taken into account for the purpose of reducing developer contributions, including affordable housing. The government intends to review this Viability Guidance and will be considering whether there are circumstances in which site-specific viability assessment may be taken into account, for example, on large sites and Previously Developed Land.

And - an important new boost at §158:

“A proposed development which complies with the Golden Rules should be given significant weight in favour of the grant of permission.”

N.B. that significant weight applies whether your site is in the grey belt or not.

Data centres, logistics, renewables

We have the expected, positive name-checks for data centres, grid connections, storage and distribution. More significant weight to renewable energy, as you’d expect. To go along with streams of positive SoS call-in / recovery decisions for these kinds of development all over the country in the last few months.

Flood risk

I’ve been banging on about the many risks in this area for months. To anyone who will listen [And also to people who won’t, Ed.]. A couple of helpful steps forward in this area of policy - albeit there’s still a distance to travel:

A new narrow but important exception to the circumstances requiring a sequential test:

“175. The sequential test should be used in areas known to be at risk now or in the future from any form of flooding, except in situations where a site-specific flood risk assessment demonstrates that no built development within the site boundary, including access or escape routes, land raising or other potentially vulnerable elements, would be located on an area that would be at risk of flooding from any source, now and in the future (having regard to potential changes in flood risk).”

NB I’ve already seen many bits of commentary from learned folks which interpret this paragraph - particularly the “now and in the future” bit - as allowing mitigation measures (i.e. accounting for the impacts of your development) to be relevant to whether you need to do a sequential test or not. Well. We’ll see. But, fwiw, coming from someone who would’ve been broadly supportive of a change like that, that is not how I’ve read it. NB, fwiw, the consultation response which says:

Whether the policy has actually achieved that clarity is another issue - it would seem from the early reviews that it hasn’t. Anyhow… all of which is still going to mean - many, many cases will still require sequential tests, even on account of pretty measly bits of perfectly fixable e.g. surface water flood risk. Sigh. An opportunity missed?

Watch this space for new flood risk sequential test PPG on what a reasonably available site is. And ultimately, this is a topic which will be the subject of National Development Management Policies next year.

We get welcome confirmation that “where planning applications come forward on sites allocated in the development plan through the sequential test, applicants need not apply the sequential test again.” Not clear how that idea plays when e.g. the allocation was not itself based on a sequential assessment that considered flood risk from all sources.

N.B. that even if you have to do a flood risk sequential test, and you don’t pass it, the High Court confirmed in the Redrow/Mead case (links here) that if e.g. there is a substantial need for housing which could not be met entirely on sequentially preferable sites, so that additional sites with a similar or worse flood risk would need to be developed, less weight might be given to this issue. Just like the Secretary of State did with the recent decision granting permission for a new prison in the green belt in Lancashire (link here). If the sequential test doesn’t add up to a “strong reason for refusing development” within the meaning of §11(d)(i) - which is, in the end, a planning judgment call - you’re not excluded from the grey belt definition by e.g. a bit of surface water flood risk arising on your site.

Beauty

Is not ditched as a high-level aim altogether, but the focus is (much more sensibly - as I explained e.g. here) on high quality design - to be achieved through coding and guides. The fundamental presumption - “development that is not well designed should be refused” - remains intact. Conversely, significant positive weight goes to development that reflects local design guidance.

Plus, in a win for common sense, the old §130 is gone, so we no longer have the suggestion that uplifts in density “may be inappropriate if the resulting built form would be wholly out of character with the existing area”.

Highways

The core test of severity is amended in a clever but powerful way at §116:

“Development should only be prevented or refused on highways grounds if there would be an unacceptable impact on highway safety, or the residual cumulative impacts on the road network, following mitigation, would be severe, taking into account all reasonable future scenarios.”

Those reasonable future scenarios are defined in the glossary as:

“a range of realistic transport scenarios tested in agreement with the local planning authority and other relevant bodies (including statutory consultees where appropriate), to assess potential impacts and determine the optimum transport infrastructure required to mitigate any adverse impacts, promote sustainable modes of travel and realise the vision for the site.”

In a nutshell - no more inane wrangling over unrealistic theoretical worst cases. Is the idea. Plus a requirement for transport assessments to be “vision-led”. Which is defined as “an approach to transport planning based on setting outcomes for a development based on achieving well-designed, sustainable and popular places, and providing the transport solutions to deliver those outcomes as opposed to predicting future demand to provide capacity (often referred to as ‘predict and provide’).”

So. There are just a few of the headlines. Are you still with me?

Now… at last… to the important bit. The gongs…

🏆 Best Planning Policy of the Year 🏆

It’s a crowded field this year [haven’t been able to say that for a while, Ed.] but, in the end, the judges were unanimous. Can I have the envelope, please … Yes, in 2024, the award for the best planning policy of the year goes to:

§146 of the new NPPF.

Which says (as above) that:

“Exceptional circumstances include, but are not limited to, instances where an authority cannot meet its identified need for homes, commercial or other development through other means. If that is the case, authorities should review Green Belt boundaries in accordance with the policies in this Framework and propose alterations to meet these needs in full, unless the review provides clear evidence that doing so would fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt, when considered across either the area of the plan or the wider Green Belt as a whole.”

Why, in the opinion of our judges, did this apparently modest paragraph win out?

For the converse to all the reasons the opposite policy won worst reform of the year in 2023. Michael Gove’s version of this policy was, in the end, a recipe for stagnation. Planning not for the future, but to freeze ourselves into the past.

This year’s winner is the opposite. In the end, planning is about priorities. And what we have here is a policy which prioritises people. Meeting their needs. Rising to their challenges. Putting a permanent roof over their heads. By doing what planners are supposed to do… reviewing boundaries. It all starts with reviewing our boundaries. Assess our needs. Consider whether we can meet them. And, if we can’t meet them, re-draw the boundaries. Make changes to accommodate… us. All of us.

Will the green belt perish on account of all this reviewing? No it won’t. As we know, in the last decade, the amount of green belt land in England has gone… not down… but UP. Overall, the total area has barely changed in decades. And at the current rate of so-called deterioration it’s not going anywhere for the next millennium or so. But it’s time - isn’t it - surely now it’s time to revisit the creaking policy mechanisms of the 1950s, not to trash them, not to bin them… but at the very least… to review them. And to change them when we need unremarkable areas of land to house our people. To meet needs. And to meet them in full. If we aren’t at least trying to do that, what on earth are we doing?

So. §146 of the NPPF. Take a bow.

And - to be a little serious just for a moment - lots of policies in this document are really very impressive. We’ve had some moments in the last few years where NPPF consultations have really made you wonder what it’s all for. This is not one of those moments. This national policy proposal is not borne out of a defensive political crouch. Not just a ploy to keep the Theresa Villers brain trust at bay. In the round, for my money, this is a policy, a proper policy, that comes with a vision, that comes from a clear and unapologetic desire to make absolutely enormous change. Urgh. A vision. We haven’t had that for a while. These proposed changes are serious. They’re thorough. They’re deeply considered. The overall ambitions for delivery remain (very) lofty. So lofty we may not get there, at least in the first parliamentary term of a Labour Government. But, heck. Maybe now’s a time for some lofty ambition.

🏆 Worst Planning Policy of the Year 🏆

It can’t all be motherhood, apple pie, peaches and cream. Sorry folks. Something always has to lose. And this year, the loser is…

The NPPF’s transitional provisions for plan-making in Annex 1 (summarised above).

Why?

Well, I’ve explained it already here:

On the one hand, the Government doesn’t want the new NPPF to totally up-end proper plans which are in their later stages toward adoption. Fair enough, right? And having a plan - even a bad plan - is better than having no plan at all - isn’t it? Well, isn’t it?

There’s another side to this: all over the country, in the last couple of months authorities have been fast-tracking - sometimes at breakneck speed - their local plans through Reg 18 and Reg 19 consultation processes in a desperate rush to get a plan, any plan, submitted to the Planning Inspectorate prontissimo for examination before the new NPPF is adopted. In an effort to, you guessed it, avoid having to plan for these tough new numbers. Again, what hope for our 1.5million target. What hope indeed. Alas.

So why, then, do the transitional provisions take the biscuit this year? Well. Because, under these provisions, some of those wayward authorities might actually end up getting away with it. And here’s what I think:

We’re either serious about increasing housing supply or we’re not.

Now. Whether we are or not is, in the end, a political decision. But it’s a decision this Govenrment has already taken. This Government was swept into a landslide victory on a manifesto - which I wrote about here - that promised 1.5 million homes over this Parliament. That’s what it’s after. Building on a scale we’ve not come close to for many, many decades.

Getting there, or even close, is going to be massively difficult. Obviously. Doing it sustainably in the long term is going to require rolling out strategic planning at a regional or city-wide scale, but we’re nowhere near achieving that nationwide. Not yet. It’s going to require universal local plan coverage, but again - we’re nowhere near that either.

And it’s not always the case that “any plan is better than no plan”. Not when local plans have been so successful in baking in housing targets that suppress what the true levels of need actually are.

The boost - see above - from 2026 to (in effect) a 6 year housing requirement rather than 5 for some of these authorities trying to dodge their responsibilities is a welcome and clever bit of balance, but many of these authorities will even then still be insulated from the consequences of their failures (even in the face of shortfalls in delivery) by the very policies that have stopped them planning properly in the first place (e.g. green belt).

So. What do I think? I think that whatever your views are on whether these new housing numbers are a good idea, the real risk is that under the NPPF we may not find out if this new scheme is actually going to work or not. The risk is it not being allowed to take effect, not widely enough or quick enough to make enough of a difference - within this Parliament, or beyond it. And that is because the policies on 5 year housing land supply and the transitional provisions allow very much lower housing numbers to be baked in, including in London for now under the existing London Plan. You want change? Real change? Fast change? You’re interested in 1.5 million homes - really? Well, ok. Then these so-called mandatory numbers need to get an awful lot more mandatory much, much quicker.

Let’s hope - let’s all hope - that those fears turn out to be completely, utterly, flat wrong. If not, the real answer to all of this may lie in more active interventions from the Minister in plan-making. Which ain’t easy. But, heck. This Government has a target to meet. And you can’t make an omelette without etc. etc. So… it’s lucky we have some new PPG on local plan interventions! My guess is that we can expect to see those powers to be flexed more regularly in the next couple of years.

🏆 Worst Planning Headline of the Year 🏆

Now, look. You can accuse the judges of recency bias all you like. It’s been that kind of a week. But yesterday’s headline from the Telegraph… in the end it just can’t be beaten (text of the article here if you have the stomach for it):

I mean. Really? I don’t know why we bother responding to this kind of thing any more. But - obviously - nothing in any of these proposals even remotely corresponds to this headline. It’s just the kind of deliberately misleading, mendacious, tendencious claptrap that is designed to anger us, divide us, confuse us and set the planning system on itself. In other words - a 100% unanimous hit for this award.

Well done to everyone at the Telegraph. Another stellar day’s work keeping your public informed. Enjoy the award!

And just like that - it’s almost over. What it’s year it’s been. Good luck out there, #planoraks. Learning your new paragraph numbers. Getting to grips with it all. There will - for better or for worse - be many thousands of seminars, webinars, roundtables and everything else to get your fully caught up before long.

And now that we have it all, here’s to 2025 - when, as a group, as a team, as #planoraks united, we start the daily grind of making the high-minded objectives of this document a reality. One plan at a time. One scheme at a time. One house, wind turbine, data centre or solar panel at a time.

Next year, who knows! More PPG. National development management policies. Leading to further NPPF tweaks. A Planning and Infrastructure Bill. A devolution white paper (coming before long). The new towns task force reporting. I mean… life for #planoraks isn’t exactly going to slow down. But in the meantime, it’s probably just about time that we start to slow down. Just a bit. So - with that in mind:

Merry Christmas, friends, happy holidays, and have a wonderful new year. Stay well, #planoraks. God bless us, every one. And - whatever else you do - now more than ever, remember to #keeponplanning. And rest up: we’re going to need you in 2025. Someone’s got to work out what this new NPPF means!